Editorials

Artist Review: Guillaume Sardin

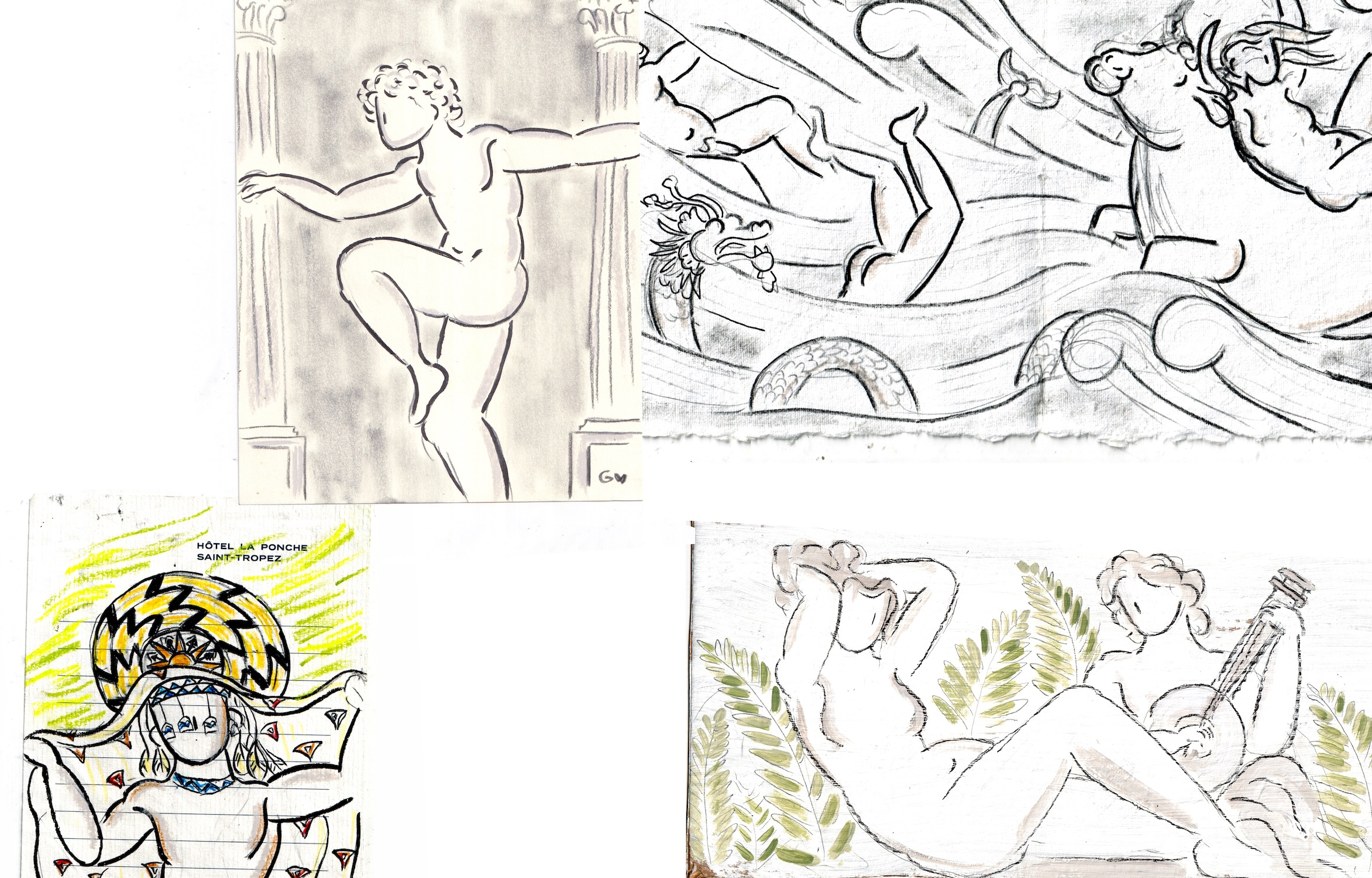

Guillaume Sardin occupies an artistic space of wonder that is at once disciplined and childlike. A space where the warmth of a human hand overrides digital perfection, and the characteristic whimsy of his “narrative drawings” belie the deep skill that goes into the studied relaxedness of every line.

Guillaume Sardin occupies an artistic space of wonder that is at once disciplined and childlike. A space where the warmth of a human hand overrides digital perfection, and the characteristic whimsy of his “narrative drawings” belie the deep skill that goes into the studied relaxedness of every line.

His work is characterized by a precision that betrays his architectural roots mixed with a curiosity about the world’s hidden corners and untold stories of the past. It has already found a place within the Lebled Soloviev Editions catalogue: those who have received recent correspondence may have already encountered Sardin’s vision through the poster he designed for us — a subtle introduction to an ongoing collaboration culminating in a landmark book scheduled for late 2026.

Although the details of the forthcoming volume are still in development, it is already clear that it is not intended as a mere retrospective of past work, but an entirely new project in its own right. Sardin is imagining a “what if?” exploration of an imaginary world, a sort of paper architecture made from a mixture of mythology, ink and thought about a counterfactual world, where, for instance, Cleopatra won the Battle of Actium. We can’t wait to see where he takes it.

Guillaume Sardin’s work tends to be as profound as it is playful. He grew up in Nantes in a family of “makers” — both parents were highly creative individuals. Other family members too were craftspeople: drawers, carpenters, sculptors, painters.

“I grew up in an environment where things were made by people I knew,” he says, and this infused him with the belief that the world is something that can be constructed and handled. Undoubtedly this has played a part in his technical refinement through constant practice. Even now, he experiences his skill as “a muscle, rather than a muscle memory… like working out. If you stop for a few weeks, you get rusty.”

Yet his perspective has been broadened by a restless creative wanderlust that took him early in his architectural career from France to New York to Rwanda. It was in these transitions that his editorial philosophy began to crystallize, often centered on what he describes as "echoes from the past." Sardin is a listener of history, but he is particularly attuned to the frequencies that are often suppressed or unwittingly ignored. He looks beyond the hegemony of white Western narratives, seeking the stories of the people who were not the "winners" of history — those marginalized voices and the cultures that are often edited out of the dominant canon.

Mythology plays an essential role in cultural truth. For Sardin, a myth is not a falsehood; it is a narrative that a culture tells itself to explain its place in the universe. Like Tarot cards — another point of interest that we may see crop up in Sardin’s book — mythology helps us to tell a true story about ourselves, even if the details of the narrative are not strictly factual. It is a lived truth from one perspective that is often more revealing than a dry list of historical facts. In his work, he blends this historical detail with mythological wonder, creating a space where the viewer can engage with the world’s complexities without the burden of a single, prescribed interpretation.

History, as he sees it, is not a static record but a series of layers, or "echoes of echoes." He is especially fascinated in how representations of the past eventually become part of the canon in their own right. The Bloomsbury Group is a prime example; he is entranced by the Charleston Farmhouse, in which young artists like Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant “tattooed their old house with paintings… basically a Tudor or an Italian fresco, painted in the 20th century”.

This layering, where the interpretation of a moment has become as significant as the original moment itself, is a recurring motif in his work. Sardin is interested in how a creative act transitions from a lived experience into a cultural landmark. There are multiple moments that recur, linked along a timeline, and who is to say that one is any more important than any other?

This interest in multiplicity extends into the realms of biodiversity and human diversity, which Sardin views as inextricably linked. To him, the health of a natural ecosystem is reflected in the health of a cultural one. A world with only one story, one voice, or one way of seeing is a world in decline. He uses his art to advocate for a richer, more diverse landscape, both literal and metaphorical. By documenting a wide array of human voices, histories, and natural forms, he creates a visual dialogue that resists the thinning of our global culture.

This focus on not losing a diverse multiplicity of voices may seem contradictory when compared with another of his interests: the idea — and impossibility — of permanence. He has a deep fascination with fallen empires, driven by the inescapable truth that every empire, no matter how grand, eventually dissolves. This is not a nihilistic view, but rather an appreciation for the inherent ephemerality of human endeavor, which he translates into his own life and work.

“We should not archive everything,” he says. “Some things should just give a memory. I like the fact that some things are temporary.”

This cycle of rise and fall is vividly expressed in his depictions of nature fighting back. In many of Sardin’s compositions, one senses a quiet uprising of the natural world. Perhaps our current "empire" — the modern, industrialized world — may not be overthrown by a rival group of humans, but by nature itself reclaiming its territory. It is a vision of landscape or space as the ultimate successor, a silent force that waits patiently beneath the pavement or behind the clouds.

At the heart of Sardin’s inquiry, of course, is the question of who gets to define "truth" and the inherent contradiction in there ever existing a definitive story, human or natural.

“The only story we can tell is our own story,” he says, musingly. And this, inevitably, will be superseded by another vision, an interpretation of our own narrative. His book, of course, will not last ever, for nothing does. But for the time it endures, we’re looking forward to seeing what story Guillaume Sardin tells for us. And perhaps even more so for the art it will inspire — the “untold stories” in the future.

MaelleSaliou%20(5).jpg)